The Ideal of a University: A Philosophical Consideration in Light of Modern Educational Revolutions

by Dr. Peter Redpath

Peter Redpath

We meet today to start to plan a new renaissance in Western university education. In so doing, we engage in a historic moment. At such a time, we do well to recall Aristotle’s sage admonition that a small mistake in the beginning multiplies later on and Étienne Gilson’s prudent observation that we think the way we can, not the way we wish. We meet to articulate practical principles based upon abstract considerations of the nature of a university. If the principles we derive are right, if we have precisely extracted them from the natures of things, not from unrealistic dreams or ungrounded imaginings, and if we and others in the future apply them prudently, with logical consistency, to the practical order, with a lot of good luck, or better, Divine guidance, what we plan to establish will be well-founded, flourish, and help to improve our culture.

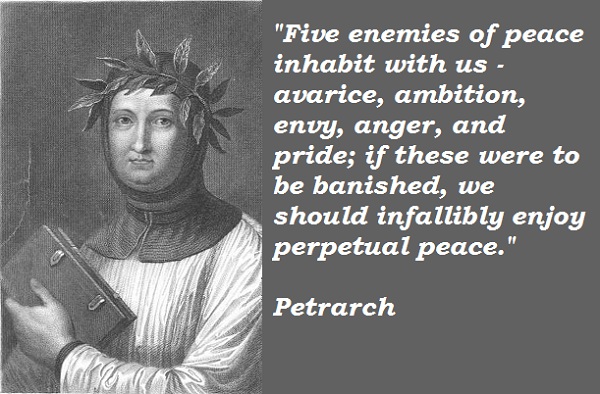

Failure to extract right principles from the being of things was the precise mistake made by the leading figures of the last three Western educational revolutions, Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch), Réne Descartes, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Practical action never occurs within a vacuum. In practical matters, failure to understand our surroundings, the circumstances and conditions we need to generate an action, our context, involves an mistake of serious import. Petrarch, Descartes, and Rousseau made such a mistake.

In my opinion, Petrarch’s revolution, which gave the Italian Renaissance its formal direction, started one day in Rome in 1341 when Petrarch was crowned poet laureate. The twentieth-century’s leading historian of Renaissance thought, Paul Oskar Kristeller, de-scribes this scene in a threefold way: (1) “The reading of the ancient Latin writers, and the sight of Rome’s ancient monuments, evoked in Petrarch as in many other Italian humanists a strong nostalgia for the political greatness of the Roman Republic and Empire”; (2) “the hope to restore this greatness was the central political idea that guided” Petrarch in his dealings with the Pope and Emperor, with Cola di Rienzo, and with the various Italian governments”; and (3) Petrarch had the conviction that his coronation was a renewal in his person of “an ancient Roman honor.”

Francesco Petrarca

For our purposes, a main significance of these events is that the circumstances of Petrarch’s time evoked in him a life work, a major goal. This was primarily a political, not an educational, project: to revive the greatness of the Roman Republic in a Christian-ized form. To do this Petrarch needed to change the direction of education. To do this, he had to revive an interest in reading pagan writers, especially rhetoricians and poets. To do this, he needed, in turn, to elevate the status of poets and rhetoricians in the university and within the eyes of the Church. To elevate this status, he took a commonly traveled road in the history of human thought: He sought to increase the status of the disciplines of poetry and rhetoric within the order of human learning and the eyes of Church authorities by decreasing and deconstructing other academic disciplines, especially some versions of scholastic theology.

By taking this road, wittingly or unwittingly, Petrarch did several things that, educationally, doomed his project to fail. He subordinated the goals of education to the goals of politics, something against which Plato wisely warns us in his discussion with Callicles in his dialogue the Gorgias. By doing this, Petrarch (1) made educational institutions instruments of, and subservient to, sophistry; (2) subordinated philosophy to rhetoric and poetry; (3) violated a metaphysical rule that Gilson says repeats itself in history: Philosophy always buries its undertakers; and (4) revived academic disputes going back for centuries, to Plato’s time and beyond. Faculty of arts in the monastic and cathedral schools, and among members of the faculty of arts, as the famed “battle of the arts.” This fight was a continuation of the age-old battle between philosophers and poets that Plato described in Book 10 of his famous Republic. For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church had not encouraged reading of pagan poets. In the Medieval trivium poetry was not even a separate division. The division was grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Because of extensive illiteracy during the Carolingian Renaissance, grammar and rhetoric played a more important role in the schools than did poetry. They tended to absorb poetry. After the eleventh century, poetry was taught within the liberal arts division of rhetoric as part of the art of letter writing [ars dictaminis]. Still, it was largely the Cinderella of the liberal arts.

By taking this road, wittingly or unwittingly, Petrarch did several things that, educationally, doomed his project to fail. He subordinated the goals of education to the goals of politics, something against which Plato wisely warns us in his discussion with Callicles in his dialogue the Gorgias. By doing this, Petrarch (1) made educational institutions instruments of, and subservient to, sophistry; (2) subordinated philosophy to rhetoric and poetry; (3) violated a metaphysical rule that Gilson says repeats itself in history: Philosophy always buries its undertakers; and (4) revived academic disputes going back for centuries, to Plato’s time and beyond. Faculty of arts in the monastic and cathedral schools, and among members of the faculty of arts, as the famed “battle of the arts.” This fight was a continuation of the age-old battle between philosophers and poets that Plato described in Book 10 of his famous Republic. For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church had not encouraged reading of pagan poets. In the Medieval trivium poetry was not even a separate division. The division was grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Because of extensive illiteracy during the Carolingian Renaissance, grammar and rhetoric played a more important role in the schools than did poetry. They tended to absorb poetry. After the eleventh century, poetry was taught within the liberal arts division of rhetoric as part of the art of letter writing [ars dictaminis]. Still, it was largely the Cinderella of the liberal arts.

This brawl would erupt during the twelfth century as the Cornifician contorversy at the cathedral School of Chartres and the monastery of St. Victor in Paris. At this time, the humanist John of Salisbury, William of Conches, and Hugh of St. Victor had gotten involved in a dispute related to the work of an unnamed author whom John of Salisbury had apparently dubbed Cornificius, “an opponent of Vergil.” The fight involved charges and counter-charges of heresy and watering down the school curriculum. John and others were especially concerned about the rise of the status of dialectics in the schools and monasteries, and the failure to read the “authors” or traditional “authorities.” This dispute would spill over into the thirteenth century in Paris, where Henry of Andelys would describe it in his Battle of the Seven Liberal Arts. Petrarch would revive and redirect this dispute during the fourteenth century. As famed literary historian Ernest Robert Curtius rightly notes: “Between the world of John of Salisbury and the world of Petrarch there is an intellectual kinship.”

Descartes’s educational revolution is incomprehensible apart from understanding Petrarch’s dream. Descartes’s revolution is a moment in Petrarch’s political project, a continuation of the battle of the arts from a fight within the trivium to a battle between the trivium and the quadrivium. In my opinion, because intellectuals within Western culture have failed accurately to locate Descartes’s revolution within Western intel-lectual history, we find it difficult to extricate ourselves from the cultural mess into which we have fallen as a result of logical application of Cartesian and Enlightenment principles to our educational institutions. Strictly speaking, Descartes was no philosopher, and the revolution he initiated was not philosophical. It was a humanist revolution, a continuation of the Battle of the Liberal Arts, most precisely among rhetoric, poetry, logic, and mathematics, going back through Descartes to Petrarch. Hence, in its roots, Descartes dream is an extension of Petrarch’s dream, a political project designed to enhance Western culture by elevating logic and mathematics over all the other arts by reducing all the arts to them.

Descartes got involved in this dispute because, centuries before him, to elevate the status of poetry and rhetoric over scholastic theology and philosophy, Petrarch had fabricated a story about the nature of philosophy that he had gotten through Medieval encyclopedists, like Cassiodorus and Isiodore. They, in turn, had gotten the story from St. Augustine, who had inherited it from Philo Judaeus through the teachings of St. Ambrose. According to this fabricated history, philosophy is a hidden teaching, an esoteric metaphysical and moral doctrine that Moses had initiated. Supposedly, according to the story, this teaching had been transmitted by Moses to posterity through Scripture and the work of pagan poets and philosophers, especially Plato and Vergil.

By the end of the Renaissance, this fabricated tale about philosophy’s origin had helped to elevate the status of poetry and rhetoric within many European universities and conflate theology with philosophy, and philosophy with poetry and rhetoric. It also stood as an obstacle to the development of mathematical science, especially within the schools of the Jesuits.

This was the context in which we must understand the significance of the dream of Descartes to have discovered a wondrous system of science of clear and distinct ideas, buried in the hidden recesses of the mind. Descartes’s revolution was primarily directed against Renaissance humanism and toward a new mathematicized humanism. Yet it built itself upon Petrarch’s fabricated notion that philosophy is a hidden teaching. It simply rejected the historicist grounds for this teaching. This is the context against which we have to understand the educational revolution of Rousseau and the Enlightenment. In his famous work Émile or On Education, Rousseau completes the trinity of the modern educational revolutions. Rousseau does this by reconstituting the Cartesian project by returning the notion philosophy to its historicist, Petrarchian and poetic origins.

As part of the discovery of science completely whole in his mind as a system of clear and distinct ideas, Descartes could not account for communication between substances. He could not explain how mind and matter interact. Rousseau solved this problem by getting rid of the notion of matter and of Descartes’s claim that, through application of simple Cartesian doubt, we find the system of science whole and complete in our minds. Rousseau turned matter into spirit and declared that, while science is a system of clear and distinct ideas, we discover it historically, not through Cartesian doubt. Instead, we find it through conflict with poetic projections of our emotions, or what a contemporary Heideggerian would delight in calling our “projects.”

For our purposes, we need to understand that our contemporary Western educational institutions are the result of the application to the practical order of Enlightenment principles about the nature of philosophy and science. These Enlightenment principles gave birth to our modern public schools and universities. And the undergraduate and graduate education programs from these universities, plus the views of human nature popularized therein, and in disciplines of psychology, sociology, philosophy, biology, and others, have invaded our Catholic and non-Catholic educational institutions. They threaten their identity and health and the future well being of our democracy. In short, mainly under the influence of Rousseau’s and Descartes’s disordered notions of science, the Enlightenment project unwittingly, and despite any and all claims to the contrary, gave birth to educational institutions that are essentially religious and sophistic forms of neo-pagan, neo-gnostic, spiritualistic fundamentalism. These arose as the necessary means for engendering the poetic metaphysical ground of modern science.

The reason why this must be so is clear. Under the influence of Descartes, Rousseau, and their progeny, modern physical science seeks to be intellectually all-consuming, to replace metaphysics as the highest form of human learning. No philosophical metaphysics can justify this pursuit. So, the modern scientific spirit turns to poetic myth, sophistry, and fundamentalistic spirituality to create the metaphysics it needs to justify its all-consuming nature. In practical terms, this means that, if universities are primarily institutes of higher education, and metaphysics is the highest form of human education, the modern scientific spirit necessarily inclines us to create institutes of sophistry to justify its claim to be the highest mode of human knowing.

Most critics today correctly call these neo-gnostic religious principles “secular humanism.” They wrongly call them a “philosophy.” Educationally, under the influence of Rousseau, these principles maintain that all learning is revelation, a revelation of the something they call the “human spirit.” By “human spirit” they do not mean some sort of irrepressible emotion to greatness within the soul of every individual. They mean some sort of universal scientific spirit (the spirit of progress, of true human freedom, of the human project) that grows by first revealing itself in forms of backward Scriptural writings and organized religious practices. This is the same sort of universal, anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic spirit that was a main cause of the development of Fascism, Nazism, and Marxism. To help us grow beyond these backward forms of religious understanding, Enlightened intellectuals think they must encourage students to question parental authority and must attack religious traditions as backward. They call this attack against authority “tolerance” and “questioning belief systems.” As a result, contemporary public schools have largely degenerated into neo-pagan religious institutes, schools of sophistry, re-education camps, to indoctrinate these Enlightened religious principles into students to foster the growth of true, progressive science from backward religion. Today, wittingly and unwittingly, many of our Catholic schools ape these institutions. We meet, today, to get out of this neo-gnostic mess and move the direction of education back to its proper pursuit: wisdom.

Plato

Toward the end of Plato’s dialogue the Gorgias, Socrates tells the sophistic politician Callicles that a major difference exists between the lives of a philosopher and a sophist. The sophist denies the reality of good and evil, truth and falsity. For the sophist, man is the measure of all things and, at best, the human good is pleasure. If such be the case, then no real art exists, and certainly no hierarchy of arts. To live the life of a sophist or a philosopher, Socrates tells us we need more than simply to exist. We must act. We must have power to pursue a life of pleasure or wisdom. To do this, the sophist must acquire the method of pursuing lifelong pleasure, the power to acquire undisturbed pleasure. He must, in short, become a panderer, a friend of despots. In my estimation, what Socrates tells us is true of individual sophists is also true of institutes of sophistry. Increasingly, since the Enlightenment, under the aim of engendering science as a system, and of creating a new political order based upon this sophistic dream, we in the West have created educational institutions suited to realize this project: institutes of sophistry that necessarily survive and flourish by pandering to corrupt politicians who help these institutes get the student loans, research dollars, and foreign students that they need to survive. This no is aberration of the Enlightenment. It is a metaphysical law: agere sequitur esse. Things tend to act according to their being.

Given this context, philosophically considered, what is the nature of a contemporary university, of a university that will help to extricate us from this mis-educational nightmare and restore learning to its proper order? Philosophically to answer this question involves philosophically to consider the problem. For the ancient Greeks, philosophy was not a logical system of ideas, and it never started as a study of abstract essences, not even for Plato. It was always born in the sensation of wonder. For the ancient Greeks, wonder was the first principle of philosophical investigation in general and in relation to all the divisions of philosophy. For the Greeks, philosophy always started as a natural act of wonder, rooted in a desire to escape from the potential damage that can accrue to us from being in a state of ignorance of being, the one, the true, the good, and the beautiful. All human beings by nature desire to know, as Aristotle tells us. By nature, we all desire to measure things, to beautify our surroundings, and most especially, to live well.

Plato

These natural desires, coupled with the fear of the real damage that we recognize our ignorance can cause to our ability to satisfy these natural desires, generate in some of us the desire to escape from ignorance. This subsequent desire originates in us in the same way that Plato tells us cities originate: through a recognition that we are not self-sufficient, that we are weak. In my opinion, by natural desire, any genuine university originates in the same way that Plato tells us an ideal city originates, or Aristotle indicates that a state develops: through a social contract rooted in natural desire for mutual self-improvement made among people possessed of skill. Just as a city grows in a sort of widening circle from the unification of familial skills into community skills, and of community skills into skills needed to build villages, towns, cities, and states, so universities are extensions of home schooling, extensions of skills we first learn through participation in families.

Historically, in the West, we see this process of growth in development of learning from the family into communities through the influence of ancient poets. Then, as villages, towns, and cities grew, professional schools of sophistry and philosophy battled with poets for the development of higher education. As education became more universal, religious fraternities gave birth to cathedral and monastic schools, to houses of study, and eventually, in the twelfth century to the first university, Bologna.

The lessons I learn from this development is that, in the West, universities arose from within widening political orders capable of supporting specific types of friendship among people possessed of specific learning skills, especially linguistic skills. The reason this occurred appears clear. Mortimer J. Adler has rightly advised us that we cannot become higher educated unless we read things that are over our heads. By doing this, we often extend our intellectual ability because this exercise requires us to “stretch our imaginations.” Before we can conceive anything, we must first be capable of imagining it. This means that a stretch of the human imagination always precedes theoretical, practical, and productive intellectual advances on the levels of conceptualization, judgment, and reasoning.

We stretch the imagination, however, through analogy, through an interplay of our senses, intellect, memory, and anticipation, through what we might well call “musings,” by comparing what is to what was and what could be. Such musings involve dreaming lofty, but possible, dreams, of what could be, but is not and has not been. Unless we dream such dreams, we cannot form the images and imaginations that great discoverers and inventors need and use to make higher educational advances. Adler tells us, too, that a great university is a university at which great teachers teach, teachers like Socrates, Plato, Archimedes, Aristotle, Sts. Augustine and Thomas, Dante Kepler, Galileo, and so on. I concur. But a great university is also an association of great learners, with great methods of learning. At the start of his Summa contra gentiles, St. Thomas tells us that the office of the wise man is “to set things in order and govern them well” and to do this about the most lofty matters: as far as possible to know the whole truth about everything that is. As the highest institution of human learning, clearly, a great, or ideal, university should have this same charge: to produce men and women of wisdom, who know as much as humanly possible about the whole truth accessible to the human mind.

A university, however, has this specific charge as a university, not as a family, or a cathedral, school. Wisdom presupposes science. Science presupposes art. And art presupposes much experience. If the wise man or woman is a person with science who has mastered the loftiest reasoning habits to be had in a specific area of human learning, then human wisdom only comes to us after much specialization. And specialization only comes to us after much generalization. Becoming wise is the work of a lifetime. Universities do not finish this life-long work. They continue students on the natural human pursuit of wisdom in a higher way: as independent learners. An ideal university, in short, ends the students need for learning by schooling. Hence, when a student graduates from such an institution, further learning by schooling should be a choice, not a necessity.

This means that university education presupposes college education, and college education presupposes much undergraduate education. Primarily, universities are graduate schools, intellectual associations that aim at specialization in areas of theoretical, practical, and productive science. At a university, through conversation with great intellects, through reading their books, we should learn to discover the first and most universal principles at work in the arts and sciences. To be able to do this we need the requisite imaginative, conceptual, judgmental, and reasoning skills to stretch our imaginations and intellects beyond the skills of a generalist. If we want to think like a mathematical, chemical, or musical specialist, we must first be able to imagine the way these people do. And we cannot learn to imagine like a specialist until, on the college and pre-college levels, we have first learned how to become good general listeners and readers. Higher education, in short, grows as a widening circle grows. All along the way, from its first beginnings until its deepest mastery, human learning involves an ever-widening and deepening interplay among poetry, in the sense of good literature, rhetoric, logic, and other forms of learning. On the highest level this interplay involves philosophy and theology.

To reach this level with maximum intensity we have to make sure to avoid confounding philosophy with one or more of the liberal arts. The liberal arts prepare a student’s external and internal sense faculties, reason and appetites for higher learning by beautifying the soul, no by inculcating highly abstract theoretical truths. The aim of an art is goodness or beauty, not abstract theoretical truth. Beauty and goodness are real qualities, perfections, as real as defects. Today, we speak about with reality of defects, of defective quality of material, with ease, but tend to shy away from referring to materials as having perfections. This makes no sense. Things cannot be defective unless they can be perfective. Beauty and goodness are qualities that perfect things. Hence, we tend to identify artists, people with skill, with people possessed of an ability to remove defects from material and impart qualities that improve a material. For example, a manufacturer who produces a beautiful quality tape recording or CD makes a material object that can convey a sound pleasing to the ear with a high quantity of intensity, a sound so pleasing that it (1) overwhelms the matter with the completeness of its goodness and, in the process, (2) shocks the human senses, appetites, and intellect through the magnitude of its natural suitability for the faculties involved. Liberal artists do a similar thing. Through their arts they remove from human faculties defects that prevent these faculties from exercising their natural acts of knowing with a high quantity of intensity. And they impart in their place beautifying qualities, habits of mind, memory, imagination, and external sense of high intensity that improve the precise exercise of these faculties in performance of their natural acts under direction of a healthy reasoning faculty.

To reach this level with maximum intensity we have to make sure to avoid confounding philosophy with one or more of the liberal arts. The liberal arts prepare a student’s external and internal sense faculties, reason and appetites for higher learning by beautifying the soul, no by inculcating highly abstract theoretical truths. The aim of an art is goodness or beauty, not abstract theoretical truth. Beauty and goodness are real qualities, perfections, as real as defects. Today, we speak about with reality of defects, of defective quality of material, with ease, but tend to shy away from referring to materials as having perfections. This makes no sense. Things cannot be defective unless they can be perfective. Beauty and goodness are qualities that perfect things. Hence, we tend to identify artists, people with skill, with people possessed of an ability to remove defects from material and impart qualities that improve a material. For example, a manufacturer who produces a beautiful quality tape recording or CD makes a material object that can convey a sound pleasing to the ear with a high quantity of intensity, a sound so pleasing that it (1) overwhelms the matter with the completeness of its goodness and, in the process, (2) shocks the human senses, appetites, and intellect through the magnitude of its natural suitability for the faculties involved. Liberal artists do a similar thing. Through their arts they remove from human faculties defects that prevent these faculties from exercising their natural acts of knowing with a high quantity of intensity. And they impart in their place beautifying qualities, habits of mind, memory, imagination, and external sense of high intensity that improve the precise exercise of these faculties in performance of their natural acts under direction of a healthy reasoning faculty.

Put in scholastic terms, higher education involves increasing habituation of the agent intellect whereby we become increasingly capable of precisely judging about different kinds of things through universal concepts that we are increasingly capable of abstracting from sense images. These acts of abstraction are the work of philosophy, not of poetry, rhetoric, or logic. As St. Thomas said centuries ago, “The seven liberal arts do not sufficiently divide theoretical philosophy” (“Septem artes liberales non sufficienter dividunt philosophiam). Nonetheless, analogous stretching of the human imagination through qualities of poetry, rhetoric, and logic, are indispensable handmaidens, necessary, but not sufficient, conditions, to developing the philosophical intellect’s increase in its ability to engage in these different kinds of intellectual abstraction.

An ideal university, in short, must be a house of studies and wisdom, a fraternal association of scholars that rightly orders the relationship among the arts and sciences so that, like Plato’s just man, each can do its own business, through its own principles, while each contributes to the development of a well-ordered person. No such institution can do this job well where the different arts and sciences do not recognize and respect what each does for the good of the whole, where the practitioners of arts and sciences do not know their respective subjects, principles, and methods, and where intellectual goals are subordinated to political agendas. If we wish to reverse the downward spiral of higher education in the West, and create a real renaissance in education, then our crucial agenda must be this: to be right about the nature of the thing we seek to bring into being and to reason prudently about its generation. If we do these things, politics will take care of itself. As Plato realized, rightly ordered institutions of higher learning will help to develop good citizens, and good citizens will help to develop good politicians and good cities. Our job at present is firmly to fix our sight on the goal at hand and, with God’s help, to set things in order and govern them well. The task that lies before us is enormous, but doable. Whatever its magnitude, we have little choice but to forge ahead. If we do not do this, who else will, or can?

Peter A. Redpath

St. John’s University

Staten Island, N.Y.